Photos of our exhibition focussed on female-led advocacy through art

Date posted: 29 September 2023

As part of our biannual rotation of the public gallery of the Constitutional Court, a new exhibition focussed on the theme of female-led advocacy through art was officially unveiled on the 9th of August 2023, National Women's Day.

The artists featured in the exhibition include Gille de Vlieg, Neo Ntsoma, Kim Berman, Neo Diseko, Lilly Oosthuizen, Sue Williamson, Anne Sassoon, Thea Soggot, Kim Lieberman, Barbara Tyrrell, Judith Mason, Tamar Mason, Elisa Iannacone, Kami Brodie, Ntombi Nala, and Thafa Dlamini.

The exhibition explores a wide range of artworks from mostly womxn artists in the CCAC, and those who depict women, depicting resistance against past and contemporary day injustices. The works of these artists encourage critical reflection and locate women's contributions to constitutionalism and human rights.

The public gallery is open to the public seven days a week free of charge. Art & Justice tours are presented by the CCAC curatorial team on the second and last Saturday of every month. Descriptive signage in the gallery enables self-guided tours.

This exhibition will be on show until mid-November 2023.

To find more information about any of the works mentioned below, search for them here.

Photographs © Constitutional Court Trust.

Left: Gille de Vlieg (1940- ) Meeting under a tree to discuss possible forced removals from land, Ntombi’s Camp, Kwa-Zulu Natal (1988).

Right: Bethesda Art Centre The Truth Tree (2006)

Left: Here a group is meeting about apartheid forced removals and homeland incorporation of Black South Africans. De Vlieg was a member of the Black Sash, a human rights organisation that was active in rural land struggles, and one of the few women members of the Afrapix photography collective, documenting the activist work she was involved with.

Right: The Truth Tree was inspired by the idea of a tree of justice found at the Constitutional Court. Fifteen women each made a leaf on which they told their own story of facing injustices in their homes and community in Nieu-Bethesda. The stories include issues of alcoholism, violence and upbringing. The bugs represent a mighty tree under attack at its roots.

Left: Judith Mason (1938- 2016) Gothic Leopard (1986- ).

Right: Kim Berman (1960- ) Alex under siege (1986).

Left: Mason’s medieval scene in a starry sky is inspired by Dante Alighieri’s poetry. The tail of a leopard transforms into a snake – Alighieri uses these creatures to represent desire, deception and sin – and its hind legs fuse into a green globe. The snake’s tongue forks into Easter lilies, marking mourning and the joy of resurrected life.

Right: Berman’s childhood nanny’s sister, who lost a child while she was caring for suburban white children, is depicted in this tribute to the Black women of Alexandra township who resisted the apartheid police. The artwork draws reference from a photograph taken by Peter Magubane and who was also a member of Afrapix.

Rose Shakinovsky (1953- ) Every Three Minutes (2009).

Every Three Minutes ismostly made from little doll’s shoes. The poignant and chilling work refers to the often-reported yet not entirely accurate claim that a child is raped every three minutes in South Africa, yet highlights the country’s extreme levels of sexual harassment and gender-based violence.

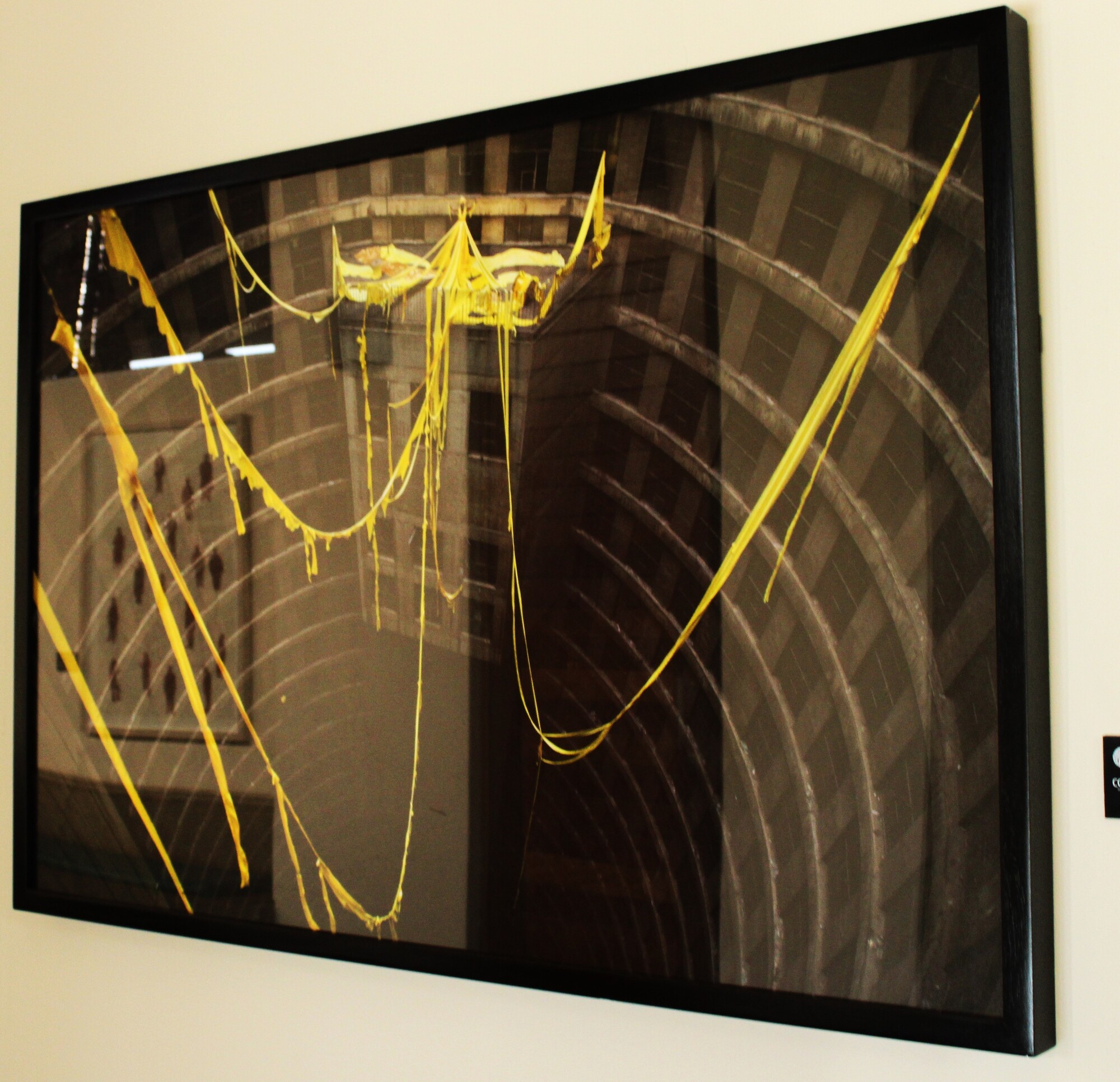

Elisa Iannacone (1988- ) The Kingdom (2018).

The Kingdom was photographed in Joburg’s Ponte Towers. A woman and rape survivor stands tall in a torn yellow dress, showing how she felt her life was ripped away from her being raped. She requested that the photograph be titled ‘The Kingdom’ as the photographic project made her feel as empowered as a queen, commanding back her self-worth and confidence.

Tamar Mason (1966- ) Flower (2004).

Flower is constructed of many hands of different skin colours. The central Black hand with a raised fist is emblematic of the resistance struggle against apartheid, while the surrounding hands speak to how people of all races fought and continue to fight against racism and other forms of injustice, coming together for a shared goal.

Eugene Hön (1958- ) Exquisite Slave, Popsy/Popsie (2009).

Exquisite Slave, Popsy/Popsie comments on the epidemic levels of predatory rape and violence in South African male prisons. A raped inmate is considered a wyfie, an Afrikaans derogatory slur. Stabbing an inmate or warden is often expected to defend one’s masculinity. Sex between men is omnipresent yet unspoken, obliquely referred to as daaiding (that thing).

Neo Ntsoma (1972- ) Amsterdam Rainbow Dress (2018).

This series of photographs resulted from a joint project between the Constitutional Court Trust, custodian of the CCAC, and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in South Africa, to present and photograph the Amsterdam Rainbow Dressin front of the Constitutional Court in December 2018.

The dress is made from the flags of all countries in the world where homosexuality is illegal, which is changed to a rainbow flag when such legislation is changed. It aims to create awareness of the persecution of LGBTIQ+ people, and is a powerful example of how art can be used to champion the cause of justice and humanity.

South Africa’s Constitution guarantees dignity and equality and outlaws persecution based on sexual and gender identities. South Africa was the first African country to legalise same-sex marriage in 2006.

The dress was modeled by transgender activist and model Yaya Mavundla.

Judith Mason (1938- 2016) The Man Who Sang and the Woman Who Kept Silent (1998).

The Blue Dress is one of the signature works of the Constitutional Court Art Collection, and relates to the telling of stories of trauma, but also to the search for, and meaning of, truth.

The executions of two anti-apartheid movement cadres by the security police, Harold Sefola and Phila Ndwandwe, as described at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), inspired Judith Mason to make this artwork.

Harold Sefola was electrocuted with two comrades in a field outside Witbank. As a dying wish he requested to sing ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’, now part of the national anthem of South Africa. His killer said: “He was a very brave man who believed strongly in what he was doing.” The braziers in the one oil painting stands as a representation of Sefola’s flame that was forcefully put out.

Phila Ndwandwe, an Umkhonto we Sizwe general, was shot by security police after being apparently kept naked and tortured in an attempt to make her inform on her comrades. It was also believed that she used a plastic bag to cover herself and preserve her dignity.

When the artist heard Ndwandwe’s story through a radio newscast, she collected discarded blue plastic bags and sewed them into a dress. On the skirt of the dress she wrote a poem to Ndwandwe, writing that plastic bags everywhere are memorials to Ndwandwe’s courage.

In 2016, a law clerk at the Constitutional Court, Douglas Ainslie, was so taken by the story of Phila Ndwandwe that he set on a path to uncover the story of her murder as documented in TRC records. He found that there was some reasons to doubt the narrative being told about the artwork, and that there had been testimonies that would make it appear that Ndwandwe was not tortured, kept stripped naked, nor (as the title of Mason’s piece portrays) “the woman who kept silent” by refusing to offer testimony.

The artist acknowledged that although the “facts” conveyed at the time of the work’s production have subsequently been called into doubt, the imagery is not meant to be read literally. Instead, the symbolism is open to different interpretations. The hyena in the oil paintings symbolise both the security police but also a psychopomp, a spiritual guide of a person’s soul.

The artwork calls upon an emotional reading in order to evoke empathy. Upon production of two additional plastic dresses in 2016 (due to the original having started to disintegrate) the artist added burn marks on one of the new dresses, using a magnifying glass, in order to signify the never-ending task of truth-seeking, as in the work of the Constitutional Court, adding another layer to the artwork.

Neo Diseko and Lilly Oosthuizen Kopano Ya Noka (Where the River Meets) (2017).

The artists relate this work to the Natives Land Act of 1913, land dispossession and the ongoing societal divides caused by racist spatial planning. Joburg’s impoverished Alexandra township is depicted alongside wealthy suburbs. A river runs through a damaged environment, yet speaks to humanity’s deep interconnectedness and a shared fate.

Willie Bester (1956- ) Discussion (1994).

In this work by a renowned anti-apartheid artist, two women converse, perhaps about their hopes for the future after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the year the artwork was made. Their unrealised dreams float in the air. The work was woven by Marguerite Zulu, June Xaba and Talita Lependo of the Stephens Tapestry Studio.

Sue Williamson (1941- ), Series: A few South Africans.

Left: Mamphela Ramphele was a founder of the Black Consciousness Movement together with her life partner Steve Biko. Apart from being a political activist, she qualified as a doctor. In 1975, she founded the Zanempilo Community Health Centre in the Eastern Cape, only to be banished to the opposite end of the country. She became an academic leader, politician, and public servant.

Middle: Helen Joseph was one of the anti-apartheid activists who read out the Freedom Charter at the Congress of the People at Kliptown, Soweto, in 1955. In 1956, she helped lead the 20,000-strong Women's March in Pretoria, protesting pass laws for Black women. Her activism led to her house arrest in 1962, which lasted for ten years.

Right: Thokozile Virginia Mngoma was a member of the African National Congress who helped to organise the noteworthy 1957 Alexandra bus boycott in Johannesburg, sparked by an increase in bus fares. For three months people did not catch buses: they walked, or rode bicycles. The boycott worked – the fares did not go up.

Left: Bongi Mkhize (1970- ) Untitled (2007).

Right: Victor Gordon (1953- ) St Edith Stein - Finite, eternal being (2001).

Left: Bongi Mkhize’s artwork is a remembrance of women's activism during apartheid, showing resilience and determination in creating a better life for themselves and their families. Women fought for independence through music, literature and art to document atrocities for the world to see, and to bring hope to fellow South Africans.

Right: Edith Stein was born Jewish but converted to Catholicism in 1922. After obtaining a PhD, she worked as an academic and later became a nun. Due to her ancestry, she was gassed at Auschwitz in 1942 as indicated by the Nazi-markings on the artwork. The Catholic Church canonised her as a saint in 1998 for her humanitarian work. The title includes her prison number and the title of her book.

Thea Soggot (1958- ) Torso 31 and Torso 37 (1996).

Torso 31 is inspired by an 11th century sculpture that has deteriorated into a limbless torso. Working in wet earth from the Magaliesberg, an area occupied by humans at least 2 million years ago, the artist explores the thoughts and emotions of early humans.

Torso 37 is constructed with layers of Magaliesberg earth. The layers cover, reveal, and inscribe both physical and psychological marks. Some layers refer to a wound as much as to healing, to pain as well as strength – an expression of life.

Thea Soggot (1958- ) Figure II and Figure II Back (2004).

The life-size female form created by using Magaliesberg earth, an area where some of the oldest hominin fossils have been found, is represented with dignity in that the image is not sexually explicit, yet fragile and intimate. Dignity is conveyed as an ancient value. The female form is visualised by textured and layered mark-making, whereas the wrinkling of the paper imitates our skin. The use of Magaliesberg earth, from the so-called Cradle of Humankind, serves as a primordial exploration of being a woman and human.

Paul Sekete (1957- ) Untitled (1994).

This artworks is in conversation with Thea Soggot's Torso (1996) and Figure II (2004). It features an experimental style that draws from modernity, while also challenging the notion that a human form should be depicted realistically. Distortion, elongation, disproportionate scale and rustic, earthy tones have been used to describe and understand the human form.

Gideon Mendel (1959- ) series: Framing AIDS.

Top Left: Thendeka Mantshi (2002). Top Right: Pumla Dladla. Bottom Left: Linda Nota (2004).

Right: Edward West (not sure about his DOB) Unknown Title (1999).

Top Left:Thendeka Mantshi discovered that she was HIV-positive when her baby was diagnosed at birth. She was a witness in a court case in which the Treatment Access Campaign challenged the pharmaceutical companies.

Top Right: Pumla Dladladiscovered that she was HIV-positive in 1997 only when her child was diagnosed with the disease. Due to a lack of AIDS education in the Eastern Cape, she did not know she could take Nevirapine to stop the virus passing to her child. She wanted to tell her story as a way of informing others of treatment efficacy.

Bottom Left: In a series, Mendel shared distressing circumstances of children who lost their parents due to AIDS in Mozambique. Linda Nota, shown, expressed difficulty in caring for her two sick granddaughters, Emilia, 7, and Carmen, 4, after the death of her own daughter. Nota was handicapped and had no income, relying on charity and the church.

Right: Inspired by Athol Fugard's play Sizwe Bansi is Dead (1972), West set out to depict the daily lives of South Africans between 1997–1999, portraying the shifting visibility of the Black community during this period of political and cultural change. As a US citizen of mixed race, he felt drawn to the liberated South Africa after apartheid.

Kim Lieberman (1969- ) Constellations (2008) (left) and Connected (2008) (right).

The leftside artwork depicts a "constellation" of eighteen, interconnected figures who have moved through the Constitutional Court. Though some of these people may have more prominent positions in society than others, one can never fully measure the impact of a single, ordinary life.

In Connected (Red) the red silk thread reminds of the lines drawn between constellations of stars and everything being connected in even the smallest of ways. The figures’ shapes are based on the artist and her husband, although they are not meant to represent any particular individual but every person.

Barbara Tyrrell (1912- 2015) series: Ethnographic drawings.

Further Left: Noble Girl- Swazi (1949) is an illustration of a girl of noble family who has an exclusive right to wear the red bird feathers indicating Swazi royalty. The feathers should be treated with extreme care. The girl’s cloth is a favourite worn over one shoulder with the same style cloth worn around the waist by men.

Left: Married Woman- Ntwana depicts a married woman from the Ntwana tribe with a helmet-like hairstyle with beaded hoops, apron, back skirt and smock-frock. Tyrrell said that the coiffure (hairstyle) is meant to denote her marriage status while the helmet-style is “older than memory”.

Right: In this artwork titled Old Lady- Sotho, Tyrrell writes that a German trader brought blankets from Bali to South Africa, which became sought after by the Sotho, as seen worn by the woman stirring the pot. Balinese influence still remains as do some very old blankets from Bali.

Far Right: Nokeri- Young Girl Xhosa depicts a young Xhosa girl from the Transkei in her daily wear, typical beaded necklace and turban style headwear, with face paint accentuating her outfit. Her bare chest denotes virginity in Xhosa culture.

Collected beadwork.

In 2008, Barbara Tyrrell donated 118 pieces of beadwork to the CCAC. Tyrrell collected the beadwork from those who sat for portraits drawn by her. Some of the beadworks were bought, and others were given to her as a token of generosity and friendship.

In her book titled Tribal People of Southern Africa (first published 1968), Tyrrell describes and studies the dress code of 25 groups within three main ethnic groups of the Southern African people (including present-day Zimbabwe). The three groups are namely: Sotho/Tswana of Botswana, Nguni, and Tsonga of the Drakensberg and Zulu, Swazi and Xhosa people of Natal. Each tribe differs in the language spoken, dress, and custom. Often, the tribes were named after the surname of their first chief. Under the main chief would be a series of lesser chiefs, each in charge of a group of families who then constituted a clan. The law of the tribe is based on custom, culture, and traditions that determine the tribe’s manners, beliefs, and ethics.

According to Tyrrell, beadwork played an important role in each tribe's belief systems, yet much of what the people wore during the time of drawing has changed or disappeared. Among the Ndebele, the disappearance of traditional wear has been slow but sure. A more drastic change in fashion was seen among the Zulu people since Tyrrell’s first journey in Zululand, now known as KwaZulu-Natal.

Traditional daily wear has been replaced with common clothes. Women’s tall head-dresses indicating marital status and tribal dresses are now worn only for special occasions, while men mostly wear their beaded ornaments on top of European clothing during celebrations. This is also relevant amongst the Basotho, who had already adopted European styles in 1948. This gave rise to the introduction of the Basotho blanket by a foreign trader. According to Tyrrell, tribes such as the Venda, Swazi, and Xhosa have managed to maintain more of their tribal ways of dressing.

Tyrrell highlights that European clothing styles played an important role in the “tribal” people’s conversion to Christianity and during the nineteenth century. “Tribal” people started considering European fashion as being synonymous with being Christian, while tribal dress and beadwork became considered as “heathen”. Beadwork use has also morphed to become part of a mixed African-European fashion sense.

In 2019, some of the CCAC beadwork was sent to beadwork specialist Hlengiwe Dube who was able to supplement Tyrrell’s notes, adding how some of the beaded items are still attached to certain African beliefs for restoration and preservation of cultural documentation.

Kami Brodie (1958- ). Left: Iris, Working Woman (1998).

Right: Three working women: Anna, Lizzie and Maggie (1994).

Left: This painting forms part of a body of work about women who were oppressed under apartheid due to their race, gender and class. Such oppression continues today. Iris is the name of the woman who worked for the artist’s mother as a domestic worker, in her Cape Town home.

Right: Anna, Lizzie and Maggie were domestic workers employed by the artist’s friends in Johannesburg and Cape Town. The artist wanted to honour those who were overlooked and marginalised on the basis of their skin colour, gender and class during the 1960s and 70s.

Ntombizodwa Somlayi, Body Map 03 (2002).

When diagnosed with HIV in 2001, Ntombizodwa recalled the car accident that had almost killed her in 1995. She added "always be prepared" as she believes one should always be ready for the worst. After getting very sick with TB and sores all over her body, she agreed to antiretroviral therapy that saved her and her two boys' lives.

Ceasar Mkhize (1970- ) and Thafa Dlamini (1978- ) Beaded Angels (2003).

The angels, who appear to be singing, were acquired for their jovial presence. In 1998, Mkhize partook in a doll-making workshop at Durban Art Gallery, where he began integrating beadwork, fabric and wire. Dlamini helped decorate the artworks with beads that her husband brought home from the workshop, a technique they have since continued.

Annie Sassoon (1943- ) Ishmael and Isaac (2001).

The artist depicts characters in a theatrical style, exploring duality and division. Her work is influenced by apartheid's politics of Othering. This work depicts the Bible's half-brothers Ishmael and Isaac; they also appear in the Koran but with their roles switched, signifying that no one truth or interpretation is absolute for everyone.

Ntombi Nala (1953- ) Uphiso (n.d).

The artist is a distant relative of the Nala family, well-known for their Zulu pottery. Her vessels are known for their large size, glossy shine and intricate designs similar to her relatives. The artist has sold many works to galleries and is represented in many collections. She also incorporates actual beadwork into some of her pot designs.