Judges interviews

Short interviews conducted with Justices of the Constitutional Court, asking them which artwork(s) in the CCAC are their favourite.

Last updated: 6 August 2024

_____________________________

Justice Steven Majiedt

Justice Majiedt with Velaphi Mzimba’s Mthokozisi(2017).

Interview extract: "I have noted that I underestimated the intersection between art and justice for a long time, simply because I was not exposed to it. So, I practised as an advocate in Cape Town for about 14/15 years, before I became a judge. There was hardly any art in that court, mostly pictures of dead judges, mostly white and male, with a picture of a Cape Dutch farmhouse, for example.

It is the same thing at the High Court in Kimberley, and the Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein. Whereas, here you are exposed to something different and you realise that art plays a meaningful role in the life of any person, but also specifically of a judge. We see some African life in all its diversity because of the range of art we have in this building. And with that, I am able to appreciate all the challenges that we have in South Africa, some which we are called upon to adjudicate. The artwork also makes you understand that we live in a wonderfully diverse country. I think it plays a role in your work as a judge to understand where you come from, and what we have in the country. It also exposes you to harsh realities of people in informal settlements, seeing their hunger and suffering through pictures and paintings. That is why I come back to this little boy and when you look into his eyes for a long time, you can see a tinge of sadness there, and it humbles you. There are many paintings around that bring out the beauty in the diversity of our country. It is not just all suffering and bad news. Together, they have an uplifting feel. I really think it is inspiring to be amongst all this art inside our building, that you do not have to go to a gallery to see all of this. The fact that the art gets changed regularly is refreshing."

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro standing outside of her home in Kimberley on 2 October 2021. Photograph by Thina Miya.

1. Please tell us about why and how you were appointed to the portfolio of decor, along with Justice Albie Sachs in 1994 when the court was housed in rented accommodation.

I think the other judges recognised our inclination towards the visual arts. And even our personal style, they probably think we're like that. And very quickly when we had to put together a committee, Albie's name and my name came up first [...] and Laurie Ackerman. Yeah, he was also part of the committee which commissioned the architects. That's where we started commissioning the architects to compete in a competition for the court building itself. And so we arranged the competition and gave the people who were going to do the brief [of] what it is that we wanted the court to look like and to represent. So after the court had been built, it became natural that we should continue to be part of the Artworks Committee. I think it is because we already understood each other and Albie and I were probably a natural choice of the judges to do this because of our personalities. You know, Judge Sachs is known to be a comfort.

2. Tell us about your first impression of the building of the Constitutional Court upon its completion in 2004. Was it what you had envisioned?

It was exciting, just what we had wanted. As you know, we were part of the committee which gave the architects the brief - the competition brief. And we had seen astonishing images of what [the] architects thought we were looking for. When we said we wanted a building which depicted the African idea of a court, some of them understood very literally and actually had the best way [pause], you know—rondavels. Of course, the court foyer does depict a rondavel, where you come in and just see everything. If you go to the area where the handmade wire chandeliers hang above the skew pillars, that is also a depiction of the African court, you know justice under a tree, a Lekgotla. And that is what we meant. It meant the idea of African openness where there is light. Africa is a hot, sunny place. Where there are no secrets. We live in rondavels, originally, you walk into a rondavel and you see everything. We were not inclined to have walls. Space belongs to all of us. When the visitors come in, they become part of that domestic space, and that's the warmth of Africa, the welcoming warmth of Africa where we don't separate visitors from family, we become one and social cohesion has always been there in Africa.

3. What were your experiences of serving as a member of the Architectural and Artworks Committee, as an academic turned judge?

Well, an academic turned judge... You know, academics tend to analyse everything. They think things through. Before they do something they must have a plan of how they imagine it will work. When we sit there and discuss, even when we hear that somebody has offered a piece of artwork to become part of the court's artwork [collection], we discuss it and look at its background and look at it. Before we even see a piece of art [or] what it should be, because the common theme that runs through the artworks at the court was indeed to promote the idea of democracy. To promote the idea of justice, to promote the idea of the Constitution itself and the Bill of Rights. And depict what would be seen as [a] South African legacy, which is art and justice. The connection between art and justice, and art which depicts either the background of our democracy, which came from the struggle to democracy. The need to [understand] what justice would mean in this new democracy is very important in accepting the artworks that should become part of the Constitutional Court and therefore part of the ideal of justice in this country. So that tune suit me in good stead.

4. How has your work on the Artworks Committee and time spent at the Constitutional Court impacted your relationship to art and architecture outside of the court?

I had a connection with art long before I came to the Constitutional Court. I had that connection when I was a child [with] creativity, visual creativity, the experience of my dad's artwork, gardening, home decor [...] So you're quite right, I grew up in a creative home and so I had that long before I came to the court.

5. How do you think art contributes to making known and accessible what the Constitutional Court does and stands for?

[...] When we collected art for the court, we did so consciously. As you say, there's a common thread throughout all the art pieces, including the integrated artworks. They depict, in various ways, our background, the background of our democracy, where we are coming from as a people, where we are now and where we want to go. What the Constitution envisions. So, that whole story is told in a particular way through every piece of artwork but together tells the same story.

5. What does the idea of a shared heritage, in relation to the CCAC, mean to you?

[...] The contribution that you all have to make in growing our democracy, that's what it is. This is our democracy. That court is our court. That court is an integral part of democracy. It represents the judiciary... in a number of ways. It is the highest court in the land.[...] And, it is the people's court. It is the people's judiciary. It is the judiciary which promotes, which protects, which advises and inspires. It's like a family. If we want the family to be functional, we all need to play our roles. And if you want that court to show who we are as South Africans, through the arts - the visual arts - then it will be for everybody.

Read the full interview here

"You cannot ignore the Constitution. It gives you a basis, your perspective gives it a bit of colour."

- Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

_____________________________

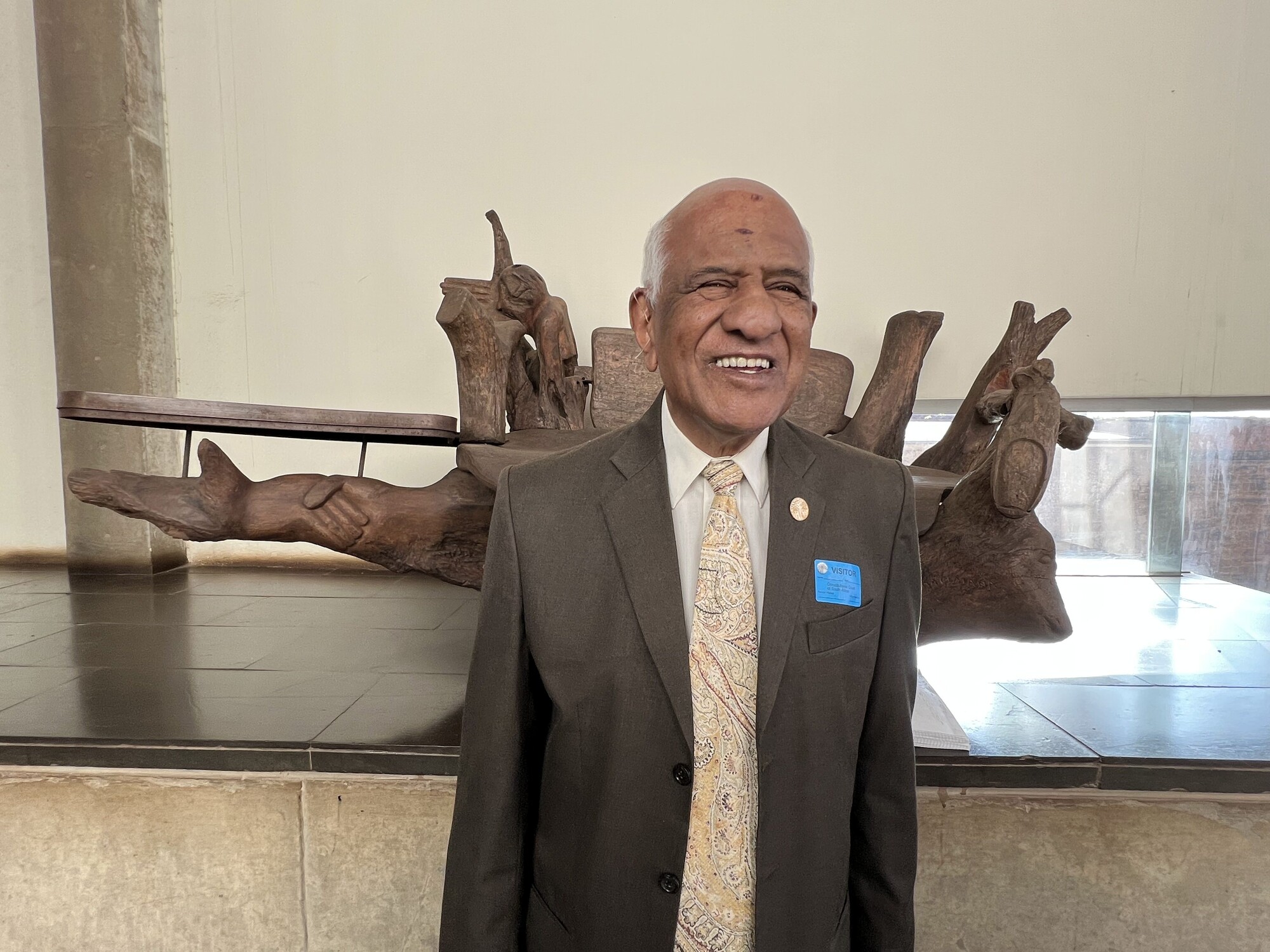

Justice Zak Yacoob

Chosen artwork: Azwifarwi Ragimana's Yacoob's Bench (2003 - 2004)

Justice Zak Yacoob with Azwifarwi Ragimana's Yacoob's Bench, 2003 - 2004, kiaat wood, 2090 x 1065 x 1105 mm. Photograph taken on 26 August 2022 in the public gallery at the Constitutional Court.

1. How often did you use the wooden bench to read braille documents, some of which you've provided to us?

I used it virtually every day. I enjoyed going out there. I very often took my sandwiches and had lunch there. And I read there almost every day, actually. Usually, whenever I had to read alone, I had material in braille to read, and I didn't have to be at the computer, and there was no phone call. I would be sitting on the bench out back. The garden was a nice area because it was so quiet. I could read undisturbed, and my PA knew that at those times, I should not be bothered at all unless things were truly urgent.

2. You mentioned that the bench meant different things to you at other times. Could you maybe elaborate on this?

Firstly, because it was very comfortable, and that I was always there. I often thought of how it was made in South Africa and how the idea of doing things in South Africa was very good. I often thought about the extent to which the court was prepared to accommodate me because of the bench and a whole range of other things. I had a braille printer at my disposal. I had a dedicated professional assistant. I thought the more employers could realise that people who could not see needed to be accommodated to do their work correctly. So the point is, this was part of my reasonable accommodation. I often thought about how spoilt I was because most people who work in other environments don't have these facilities. And that was one of the reasons why the work area was made comfortable for me, and I could produce better work.

3. Do you recall the braille incorporated onto the bronze handle of the court's large wooden door entrance as well as the braille on the concrete wall?

Yes, I do, and I wanted to say one thing about that. I think it's a good idea to show it to the public so the public understands what the braille is all about. The court should have it whether there is a judge with a disability in the court or not. It is a coincidence that it happened while I was there and because I was there. But the court needs to represent all societies in every way. In that sense, it was a good thing. The bench was a very important symbol, too, because it represents a reasonable accommodation and local talent.

4. Do you think the Constitutional Court is accessible and welcoming in its design? Or do you think more should be done?

I think it is very accessible and well designed. What they could do is change surfaces a bit more regularly. So that walking in particular— if you're walking down the long passage, then, you know, by a slight change in the surface, when you're walking on it, that you now in the area where somebody’s chambers, or something like that, you know?

I'm very interested in that point, Judge; just so that I understand clearly, you're saying the variation of the floor surface would enable you to locate yourself? So as you were moving across, you'd realise it by feeling it on the floor that you're on a bridge next to Justice Tshiqi's chambers?

You could have an effective net at a particular point? And what you can feel as well. So you make places accessible like that, yes.

That's interesting. Do you think a similar intervention could work with the railings?

Yes, the railing works; they changed the railing, especially for me. Because I found that railing is coming up and down the stairs very different when it was first made, and you walked upstairs, and when you turned one rail ended, and another rail began, at some other point there wasn't a rounded edge which made it a continuity. If you go and look at the court, you'll see on the stairs that the rails are rounded, so you can keep your hands on them when you're walking. Whereas previously, the rail ended at the top of the stairs and then started again on the passage.

Yes, I understand. This is fascinating. I'm just wondering whether wall surfaces could work as well? I'm not sure if anybody else on the team has any ideas?

Wall surfaces might work. But then it's unnatural for a person to feel the wall and walk. A rail is okay. But to feel a wall and walk is a little bit complicated.

And it might interfere with the display of artworks on the wall as well.

Absolutely, and because the artworks are so good, you could damage them as well.

5. You've already touched on how you perceive the essence of the Constitutional Court building through its design, materials and textures. Would there be anything else you'd want to add to that?

No, no, I think I'm fine with that.

6. What were your first impressions of the art and the building of the Constitutional Court when you first arrived as a justice of the court?

I arrived there at the time and the building was completely new. When I got to the court in 1998, the court was in the temporary premises in Braamfontein in a building owned by an insurance company or something. If I remember, we occupied a floor or two there, and it was good. This was a building that was constructed very carefully. One of the items on the agenda was always a report on how the court construction was going, whether we wanted anything else and so on. There's a very interesting story to that because the Department of Justice regulations proposed a toilet in every judge's chambers. We concluded that that was a waste of space and a waste of money because judges had to do the same thing that other people do in the toilet. Therefore, they could use the common toilet that everyone else uses with no serious problem at all. We then wrote to the department, but somebody asked me whether, as a visually impaired person, I needed a toilet in my own office. I said, sometimes accommodation can go too far. I was empowered to walk to a nearby toilet. What you could do and what they did for me, for example, was allocating me chambers where a toilet was right opposite my chambers. So that was a much better way of accommodation because you make it easier for the person. It made no sense to say that the blind judge must have a toilet in the chamber and the other judges do not. To come to the other point, we discussed the building, and I knew a great deal about how it was going to be and so on; how they're going to be structured, what the sizes of the offices are going to be, how many offices were going to be on which floor and so on. So by the time I got there it was just like going into a checklist and seeing whether everything was there that we had agreed would be there.

7. I have a few questions about the Constitutional Court Art Collection. Apart from the bench, is there any other specific artwork within the CCAC that is meaningful to you?

They're all very meaningful. There certainly wasn't a particular artwork that was meaningful to me. Well, now, I can't remember many of them, because if you've seen them, you'd remember them all the time. If you just have a physical description, then the reality of it is that you're likely to forget because it's not a picture in your head.

8. That's interesting. We are trying to, you know, design more braille signage for artworks that could be interacted with, artworks that could be felt and touched.

It's easy these days. You can print the description of the painting in braille and large print because people have problems with their vision in different ways. If, for example, I decided that the braille description would be pinned to the wall or something at the left-hand bottom edge of the artwork concerned? It might be a very good idea. So the person who can't see just gets to that left-hand bottom edge, finds the Braille and reads it.

Judge, is there a reason why it's very specific to the left hand? Bottom edge?

Oh, no, I was just using that as an example; but it must be at the same place in relation to each painting. That's all. And because some artworks are quite high? Yes, the bottom might be easier than the top to reach.

9. How do you see artworks as being connected to justice or human rights in South Africa, or more universally?

I think that artworks are always connected, and you could read justice into anything. And that's the point. As you know, art doesn't tell you a story directly, right. It tells you a story indirectly, mainly. So that, for example, the page has its own story, the bench has a story to tell about the relationship between justice and reasonable accommodation, the relationship between justice and simplicity, the relationship between justice and nature, the relationship between justice and local talent. So you are making the point that justice is not necessarily an international thing. It's local and International, so even the bench and any work of art with enough imagination will tell you many stories if you think of them.

10. What value, if any, do you think the Constitutional Court Art Collection brings to the court environment, the court's work, or your work?

I think it creates a particular impression of the court with the public, which is good. It creates a positive impression of the court. It shows that the court is not limited to static concepts of justice; but there is an understanding that the intellectual, emotional, and aesthetic are all part of humanity and human nature and help in the making of good court judgments. It moves away from the idea that the law report is the only thing- it moves away from the idea that judges are inhuman intellectual machines. The truth of the matter is that more and more now, we are beginning to realise that aesthetics, emotion and so-called intelligence must be balanced against each other and humanity to get the true approach from a judge concerned. So it's not only about the intellect, it's about judges having a rounded personality at every level. And the artwork provides the atmosphere for that and contributes to an atmosphere of grounded-ness. And create the impression that assures the public that the court intends to create that atmosphere.

11. We always tell the story of Garth Walker's Face of the Nation and how your handwriting inspired it alongside street traders' hand-painted signage and historical institutional signage. We then relate it to the concrete wall right behind the wall where the typefaces were installed and how each judge had to write out the phrase "human dignity, equality and freedom". Can you tell me about your experience of having participated in that?

I thought it was very important; it was a very important thing to do. It was a way of demonstrating a link between judging and the rest of the world as I saw. It was demonstrating the humanity of judges, as I saw it because it would be in their handwriting, and so on. So that was the importance of that. And I thought it was a good thing to do. I did it very slowly, and evidence that it wasn't a quick job.

Can you tell me more about the process? How did you get to figure out the letters?

I knew the shapes of letters a long time ago. I learned about them at school and so on. I used to look at signs and always ensured that people taught me those things and so on because I thought it was important for me to understand how it works.

Did you have to rewrite it in braille?

I didn't rewrite it in braille. I just knew intellectually what it was and I learned how to write, so I just did it.

Azwifarwi Ragimana's Yacoob's Bench, 2003 - 2004, kiaat wood, 2090 x 1065 x 1105 mm. Photograph taken on 29 July 2022 in the public gallery at the Constitutional Court.

_____________________________

Justice Sisi Khampepe

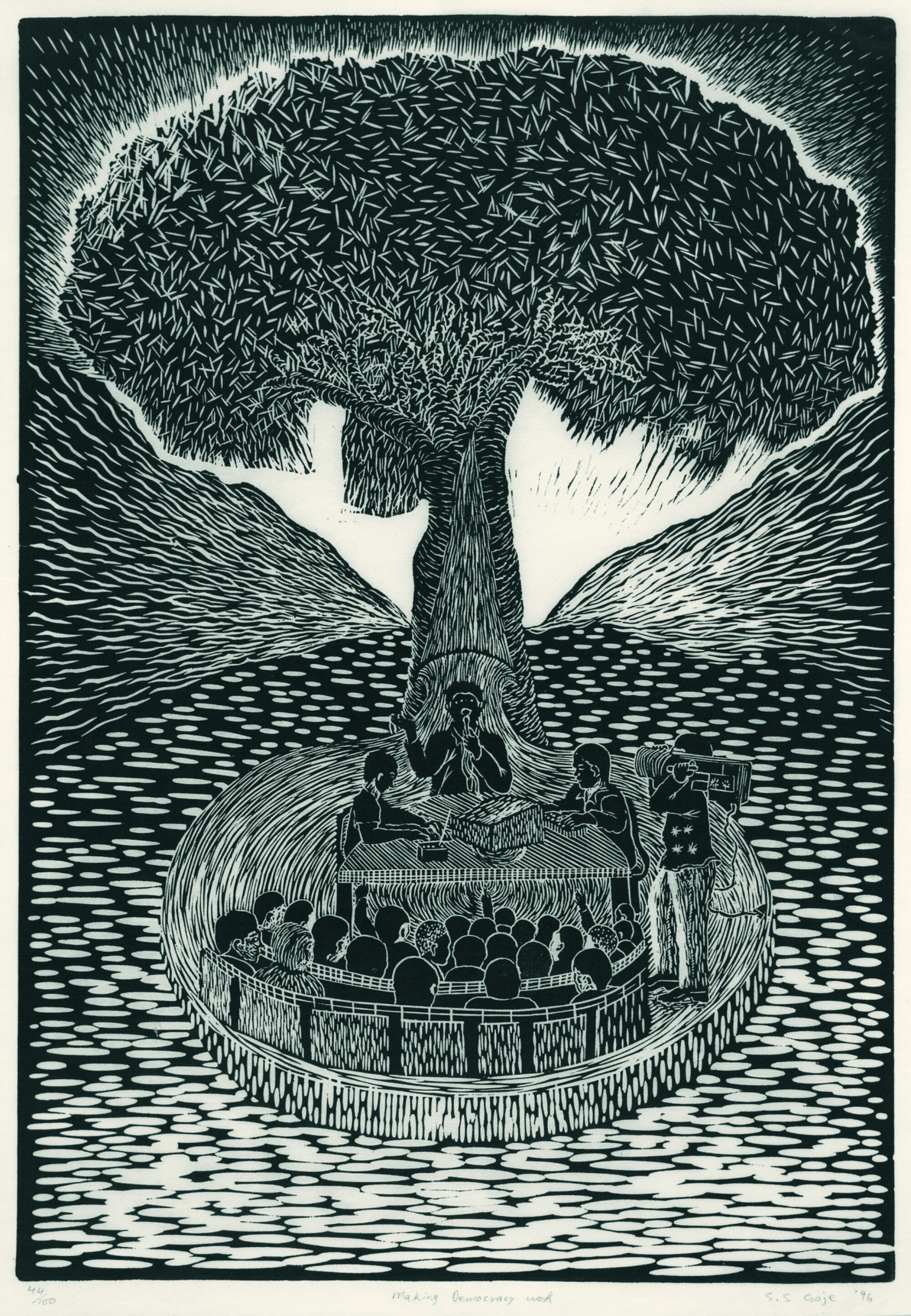

Chosen artwork: Sandile Goje's Making Democracy Work(1996)

1. Please tell us about your first impressions of the art and building of the Constitutional Court, when you first arrived as a justice of this court in 2009.

Well, to start with, I was impressed by the kind of the architecture of the building, which was different from other conventional court buildings that I knew. I was also impressed by the various artworks that adorned the building and the court’s footprint. And the fact that each chamber had a dedicated artwork and wherever you looked, there was art. There was art in the corridor, the walls, the ceilings, the floors... speaking to you. It was a museum of... an explosion of sort.

2. What led you to becoming a member of the Artworks Committee in 2012?

[Laughs] That one is quite an interesting one. Because I had been asked by my colleagues, Johann van der Westhuizen and Edwin Cameron, to become a member of the Artworks Committee, and I had refused. But then, Johann van der Westhuizen had his birthday party at his house, and he asked me to give him the greatest gift for his birthday. And that is by accepting to become a member of the Artworks Committee. And that's how I became persuaded to become a member of the Artworks Committee.

3. You became the chairperson of the Committee between 2015 to 2021. What impression did the chairmanship leave on you?

Yeah. Well, the experience of having served as the chairperson of the Artworks Committee has left me with a very positive impression. To know that with hard work, passion, determination, dedication, and fortitude, there're great rewards. I have been granted an opportunity to work with the greatest curatorial team and the best colleagues in the Artworks Committee. I couldn't have asked for more. Yes, the impression has been a very positive one.

4. Is there any specific artwork within the collection that's particularly meaningful to you?

Well, the specific artwork that is particularly meaningful to me is the one called Making Democracy Work by Sandile Goje. The linocut depicts a contemporary society embodying democracy, transparency, and community by having court proceedings under a tree. The Constitutional Court adopted the “justice under a tree” metaphor, as one of its core fundamentals, as the ceremony under the tree represents transparency and protection, and draws on the tradition of trees being community meeting places. Goje's linocut is emblematic of the Constitutional Court, suggesting a unique and open South African solution to law in a post-apartheid environment. This particular artwork tells a story about South Africa's past: the traditional community practices of gathering under a tree for conflict resolution and the administration of justice. These practices were historically marginalised in favour of the western legal system inherited from colonialism. Yet this artwork speaks to the promise of a future, an inclusive and representative system of governance, and the judiciary that embodies respect and benefits from the cultural practices and wisdom of all South Africans. It speaks to a vision of equality, both before the law and in the law itself. It represents the idea that the Constitution and the court belong to all the people of South Africa. Having grown up in KZN myself, where I experienced disputes being resolved under a tree, this particular artwork resonates with me and appeals to me. I'm a KZN girl through and through.

5. What value do you think the Constitutional Court Art Collection brings to the court's environment, the court's work or to your work as a justice of the court?

Yeah, well the Constitutional Court is in itself unique in many ways, one of which is that it is a reflection of the intersection of law, culture and democracy. The success of our democracy cannot be seen in our laws alone, it must be judged by reflecting on the culture of our country. Visual art is a representation of that culture. It is fitting then that the Constitutional Art Collection comprises a diverse and inclusive range of works, with a focus on past injustices, and the struggle that so many people of our country have endured. In this regard, there is a symbolic link between the court, our law and the art collection. In addition to the insight that the art provides on the culture of society, it is also used as a form of activism and protest. The Constitutional Court is a product of the upheaval of the apartheid regime and South Africa's new democratic chapter. It is vital to our future, but at the same time, a memorial of the pains and injustices of the past, the very reasons that the court came to exist. That's the value that I put to the Constitutional Court Art Collection.

6. What developments would you like to see with regards to the Constitutional Court Art Collection in the future?

I am very satisfied with the way it is developing.

7. How do you see art as being connected to justice or human rights in South Africa or more universally, outside of the court environment?.

Yes, I've already touched on that one. And just to say, I think here I would have to bring in the preamble to our Constitution, which commences with 'We the people of South Africa, recognise the injustices of the past, and honour those who have suffered. Since it was these words that contextualise our supreme law, there is beauty and symbolism in the fact that the court itself, the ultimate guardian and custodian of this law, is home to a collection of artwork that embodies and represents the struggle against oppression, the lived realities of our people, and the very activism that gave birth to constitutionalism. The art collection reveals what it took to build the Constitutional Court. It is only right that it is honoured by its placement in the court. Aside from the struggle that it reveals, the art collection of the court is a celebration of diversity and the collaboration of people from all walks of life. This is in any case a testament to a founding goal of our Constitution, which is unity in diversity. The art collection at the court broadens the court's accessibility by providing a form of visual jurisprudence to all visitors. In this way, it provides an alternative language, so to speak, which the court and the Constitution can be probed and be understood. In this regard, I can do no better than quote the famous words of Dr Eliza Garnsey when she said, and I quote her now: "The artworks at the court are closely connected to and blended with both the value and practice of justice. In this way, they can be understood as a new kind of visual jurisprudence. In such close proximity, the art collection inhabits a unique position where the assumptions of justice and what it means to uphold the Constitution in post-apartheid South Africa can be probed." End quote.

8. How has your work on the Artworks Committee and time spent at the Constitutional Court impacted your relationship to art and architecture outside of the court?

Yes, I now see art with an engaging eye. It has very positively impacted upon me. I see art with an engaging eye that I never had before I became involved with the Artwork's Committee.

9. Is there anything else you would like to say with regards to the art collection?

Well, safe to say that the importance of the Court's collection should not be downplayed. Raising awareness is to provide insight and understanding to all who visit the court, so that its litigants, members of the public and the tourists will know of how the court came to be here. And indeed, what it exists to achieve, and present, and prevent. It is an ode to all South Africans, that this is their court. Without them and their stories, it would not exist.

10. How does the Constitutional Court building and the architecture of the building stand out for you personally? Do you feel that it has left a lasting impression on you?

It has left a very lasting impression. I have worked through many courts as a lawyer and sitting as a judge. I have never seen such architecture. And when I saw this kind of architecture, at first, I didn't know whether I should be excited or should be angry that I'm not seeing the conventional court building. But having stayed in the court I have warmed up to the idea. It is an architecture of note. It is one of a kind. And I've only seen something that represents the Constitutional Court by the German court, the German Constitutional Court, that comes closer to the kind of architecture that we have in our country. It is a great architecture.

Chosen artwork: Sandile Goje, Making Democracy Work, 1996, linocut, 525 x 365 mm. Photograph by Ben Law-Viljoen © CCT.

Justice Mbuyiseli Madlanga

Chosen artworks: Velaphi Mzimba, Mthokozisi (2017) and Erik Laubscher, Keurfontein, Laingsburg (1995-1996)

Justice Madlanga with Velaphi Mzimba's Mthokozisi, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 1340 x 1600 mm. Photograph taken on 16 March 2020 in Justice Madlanga's chambers at the Constitutional Court. The chambers he occupies used to belong to Justice T.L. Skweyiya, whose grandchildren donated this artwork to the CCAC in June 2019, Youth Month, to honour their grandfather and his championing of children’s rights in the judgments he wrote and handed down in the Constitutional Court.

1. What aspects of the artwork make it one of your favourite artworks in the Constitutional Court Art Collection?

When I saw this artwork, I was next to the lifts on the first floor. It was on the floor leaning against the wall on the lounge-like area on the floor below. It just caught my attention and I immediately walked down to it. I decided there and then that I wanted it in my chambers. I am very happy that you obliged. What captivates me about the artwork is that the depiction is so real, so alive; the boy could just walk “out of there” and come talk to you.

2. How do you see the artwork as being connected to justice or human rights in South Africa, or more universally?

The artwork depicts a beautiful boy. We, as courts and other institutions involved in upholding fundamental rights entrenched in our Bill of Rights, owe a duty to girls and boys to enforce their rights assiduously and thus keep them beautiful.

3. What value, if any, do you think the Constitutional Court Art Collection brings to the court environment, the work of the court or your work?

The Constitutional Court’s artwork is definitely a major attraction to the court and enhances the general ambience and environment of the court precinct.

4. Is there anything else you would like to say about the Constitutional Court Art Collection?

I will comment on only one other piece that I particularly like. I do not know what it is called. It first caught my attention when I was acting here at the Constitutional Court in 2000. At the time the Constitutional Court was in the leased premises across the street. The artwork depicts a landscape. Roughly in the middle it has something that is valley-like starting from the bottom of the piece all the way up. It was positioned at the end of a longish corridor. As I walked down that corridor, the piece used to give me the sensation of continuing with my walk from the corridor onto the valley and beyond. That piece is in the present court building but it is not as beautifully located.

The artwork referred to in answer four above: Erik Laubscher, Keurfontein, Laingsburg, 1995-1996, oil on canvas, 1485 x 1930 mm.

_____________________________

Acting Justice Margaret Victor

Chosen artwork: Kami Brodie, Three working women: Anna, Lizzie and Maggie (1994)

Justice Victor with Kami Brodie's Three working women: Anna, Lizzie and Maggie, 1994, oil and acrylic on canvas, 750 x 1512 mm. Photograph taken on 17 March 2020 where the artwork was installed in the level A passageway in the administrative area of the Constitutional Court.

1. What aspects of the artwork make it one of your favourite artworks in the Constitutional Court Art Collection?

Narration on why I chose this painting:

It is in the eyes of those three women that I read the shameful history and pain of our South African past. They are a triad of sisters, domestic workers who quietly and with dignity carried the burden of apartheid and even today their full dignity not yet attained.

They are the mothers and grandmothers who sent their sons and daughters to battle apartheid often never seeing them again. They are the ones whilst earning a pittance and living in tiny domestic quarters and serving their “madams” could not hold their own children to their breast but had to send them to relatives and the desolate camps of Dimbaza, Sada, Qwa Qwa and the Winterveld where kwashiorkor was rampant with no proper protein and vitamins for the little ones.

It is these women who silently and with pain cared for the well-nourished children of their “madams”. It was these women who were entrusted with the heart of the homes, yet it is they who to this day suffer disadvantage. They continue to suffer group disadvantage and discrimination along intersectional lines. Their discrimination intersects on multi axes such as racism, sexism, lack of status as domestic workers, subjected to patriarchy, marginalisation, lack of good education because of having to leave school early to support families, poor salaries and statutory benefits.

Understanding the intersectional nature of group disadvantage of these three women illustrates vividly the structural and dynamic consequences still suffered 25 years into our democracy.

The gaze of these three women shows that they will prevail and will not be deterred, discouraged, nor dissuaded. Wathint Abafazi’Wathint’ Imbokodo – You Strike the Woman, You Strike the Rock.

2. How do you see the artwork as being connected to justice or human rights in South Africa, or more universally?

It is this artwork collection that reminds us so vividly of our apartheid history and its pain that we must never forget or become immune to. There is also a vibrancy to the collection which foreshadows hope and a better life but still tethers us to our history.

3. What value, if any, do you think the Constitutional Court Art Collection brings to the court environment, the work of the court or your work?

I think it can elevate mood, and a sense of physical well-being, as well as bolster interpersonal bonds.

Take the High Court environment – the public and lawyers who attend can be in a combative mode, or fearful of the unknown or many other emotions. I believe a meaningful art collection can help to distract in the minutes of calm before the storm. Depending on the nature of the artwork it can be grounding and reassuring.

4. Is there anything else you would like to say about the Constitutional Court Art Collection?

I feel a sense of history, stability, hope for the future and more importantly proud and privileged to sit in a building where Mother Africa showcases that she has produced sons and daughters who have so much beauty, excellence and talent.

_____________________________