The Court

The Constitutional Court was established in 1994 following South Africa’s first democratic elections and the adoption of the interim Constitution. South Africa underwent a radical transition from an authoritarian and repressive apartheid regime, founded on a system of parliamentary sovereignty, to a constitutional democracy committed to the creation of a just society based on human dignity, equality and freedom.

In 1994, South Africa’s judiciary was overwhelmingly white and male, and seen by many as complicit in the apartheid regime. It was therefore agreed upon that a new court, representative of South Africa’s diverse population and untainted by the past, should be established to protect, interpret and enforce the new Constitution.

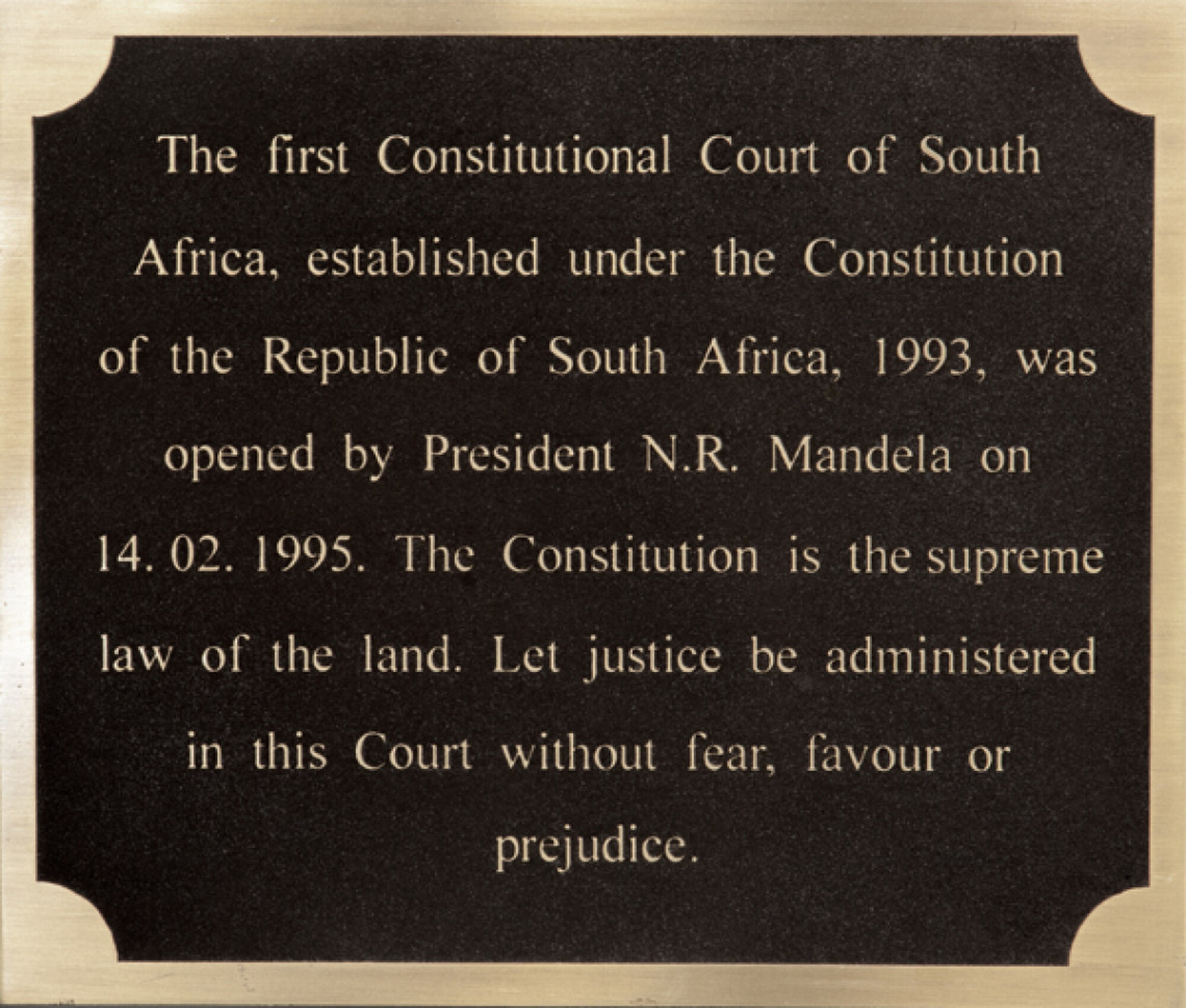

The Constitution is the supreme law of the land in South Africa. It contains a Bill of Rights that enshrines the fundamental human rights of all people in the country, and it also divides the powers and functions of government between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, as well as between the local, provincial and national spheres of government. No other law may conflict with the Constitution; all organs of state are bound by it and are obliged to “respect, protect, promote and fulfill” the rights enshrined in the document.

The Constitutional Court is the highest court in the country in respect of constitutional matters. The Court hears appeals, direct applications, confirmation proceedings (where a lower court has declared legislation invalid), and may review Bills of Parliament.

Since its establishment in 1994, the Constitutional Court has developed an extensive and internationally-acknowledged body of jurisprudence. The Constitutional Court’s mandate places it at the centre of not only the legal but also the social and political transformation of South African society. Amongst other things, the Court has abolished the death penalty, confirmed prisoners’ right to vote, required the State to recognise same-sex marriage, and declared that women are equally entitled to inherit under Islamic and African customary law.

South Africa is one of the few countries to give effect to socio-economic rights in its Constitution, including rights to have access to food, water, housing, healthcare services, social security, and education. The Court’s jurisprudence in this area is widely considered to be ground-breaking – perhaps the most famous case is Minister of Health v Treatment Action Campaign (2002), wherein the Court ordered the government to remove restrictions impeding the use of anti-retroviral drugs to combat mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

The Constitutional Court’s adjudicative role is politically sensitive, due to the fact that it exercises judicial review power over the democratically-elected organs of state and makes orders that impact state resources. In performing these functions, the Court is careful to respect the separation of powers underpinning South Africa’s unique constitutional democracy.